|

These limitations don't matter at night, because the

F-117's stealthy shape enables the aircraft to avoid detection

by enemy radar. But in the light of day, the enemy can

see the black plane against the sky, and can take aim

without the help of radar.

F-117 pilotos train almost exculsively for night missions,

and the darker it gets, the happier they are. But this

is a compromise at best. In the summer, when there are

only a few hours of darkness, a figheter like the F-117

can fly only one sortie per day. And the darkness that

hides the F-117 also hides its targets.

Air Force generals would love nothing more than a stealth

aircraft that would be invulnerable during daylight hours

as well as at night. And as POPULAR SCIENCE has learned,

military engineers are already hard at work on the technologies

needed to build such a plane. special lights, coatings,

and other technologies

|

under investigation could not only make future fighters

disappear from radar screens but could also make them

almost completely invisible to the human eye. By the early

2000s, stealth may be practical in broad daylight. Today's

experiments exploit a principle that was demonstrated

half a century ago, in a secret

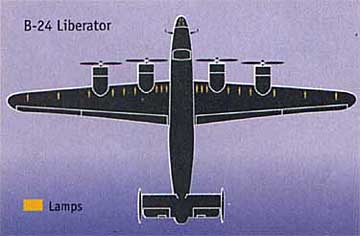

project code-named Yehudi. In that project, engineers

mounted lights on an anti-submarine aircraft make it harder

to spot against a bright sky.

Similar technology was used in the Vietnam War to shorten

the distance at which the F-4 Phantom could be detected.

Lighting systems were available when Lockheed's Skunk

Works was awarded the contract to build Have Blue, the

world's first stealth aircraft and the test bed for the

F-117A, in 1974. The breakthrough that made Have Blue

possible was the ability to reduce an airplane's radar

reflectivity to less than one-hundredth of what was considered

normal in the 1960s, slashing the effective

|

range of enemy radar. Reducing the radar reflectivity

so radically meant that the designers of Have Blue also

had to reduce its visual and infrared signatures, according

to a rule of thumb known as "balanced observables."

This rule says that a stealth aircraft should be designed

so that every dectection system arrayed against it has

roughly the same range. There is no point in building

an airplane that is invisible to radar at five miles if

optical sensors can see it at 10 miles.

Have Blue was the prototype for an aircraft that would

make its attack run at a moderate altitude of 10,000 to

15,000 feet, close enough to designate the target accurately,

but high enough to elude medium-caliber gunfire. At the

time, the designers' goal was an aircraft that would be

as stealthy in daylight as at night. The designers realized

that visual detection depends on a number of factors,

including the position

|